|

HISTORY OF CAT SPRING, TEXAS

Cat Spring was founded by German immigrants from Oldenburg and Westphalia in 1834. The settlement was named for a nearby spring where a puma was killed by one of the German immigrants.

By Leonard Kubiak, author and Texas Historian of Rockdale, texas

EARLY HISTORY OF AUSTIN COUNTY

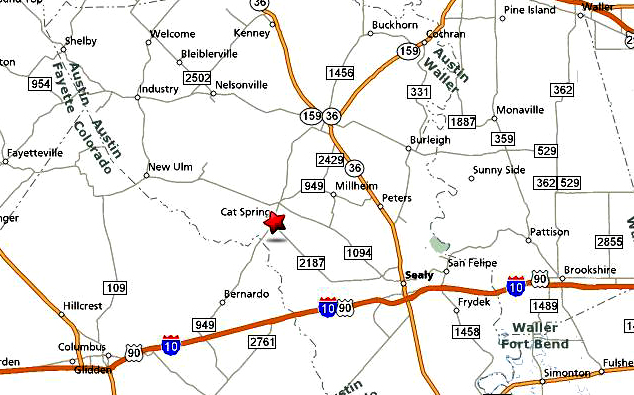

Austin County, located about thirty-five miles west of Houston, is bordered on the north by Washington County, on the east by Waller and Fort Bend counties, on the south by Wharton County, and on the West by Colorado and Fayette counties.

The county seat (and largest town) in Austin County is Bellville and the county is served by two major railways: the Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe.

The area now known as Austin County was originally selected by Stephen Fuller Austin in 1823 as the site for his colony, the first Anglo-American settlement in Texas. It was Stephen F. Austin's father, Moses, who had originally obtained permission from the Mexican government in January, 1821, to bring three hundred families to Texas to establish a colony. However, before he could begin to carry out his colonization plan he died with pneumonia on June 10, 1821. Prior to his death, Moses Austin had requested that his son be allowed to carry out this colonization plan, which Stephen F. Austin was permitted to do.

He was instructed by the Mexican authorities to explore the area on the Colorado River that he expected to settle. Austin reported back to the Mexican authorities outlining the boundaries he desired for his colony and submitted the plan he had devised for the distribution of land. In order to attract settlers for his new colony Austin advertised in newspapers and offered the incentive of additional land to those who possessed skills which could be used by all who settled in the colony. Those families which followed Austin settled on the west bank of the Brazos River, above the mouth of Mill Creek.

FIRST EUROPEAN DECENT SETTLERS IN WHAT BECAME AUSTIN COUNTY

Among the first settlers in what became Austin County were: Abner Kuykendall and sons, Horatio Chriesman, William Robbins, Early Robbins, Moses Shipman, David Shipman, William Prator, James Orrick, J. M. Pennington, Samuel Kennedy, Isam Belcher, and David Talley.

In 124 Stephen F. Austin was commissioned the political chief of the colony. In July, 1824 the general land office was opened at San Felipe de Austin, the unofficial capitol of the Anglo-American settlements in Texas. At this time titles were issued for the amount of land allowed by the contract of colonization, which was 640 acres for each single man or head of the family, 320 acres for a wife, 160 acres for each child and 80 acres for each slave. These early settlers usually built near streams where water could easily be found and an abundance of wood for building and fencing material, as well as where fuel would be readily available.

Most of the area within Austin County lies within the drainage basin of the Brazos River, which forms the eastern border of the county.

PRE-HISTORIC HISTORY OF AUSTIN COUNTY REGION

Some archeological evidence supports Paleo Indian presense in what became Austin County as earrly as 7400 B.C. During the early historic era the principal inhabitants were the Tonkawas, a nomadic, flint-working, hunting and gathering people, living in widely scattered bands, who traveled hundreds of miles in pursuit of buffalo and practiced little if any agriculture.

Karankawas, a tribe of unusually large members lived to the south and west of what is now Austin County, on the coastal lowlands. The Wacos, a southern Wichita people, also launched raids into the area down the Brazos River from their villages near the site of present Waco.

BATTLES WITH THE INDIANS

As early as 1823 Stephen F. Austin began organizing a militia with which to defend the frontiers of his colony, and the Austin County area contributed many volunteers for the Indian campaigns. Punitive expeditions were mounted against the Tonkawas in 1823, the Karankawas in 1823 and 1824, and the Wacos in 1829. The success of the militia sharply curtailed Indian depredations in the Austin County vicinity, and by 1836 they had virtually ceased. The theft of a few horses from homesteads along Mill Creek in 1839 marked the last Indian raid within the bounds of present Austin County. The Indians drifted westward and northward, and by 1850 the federal census found none residing within the county.

FIRST EUROPEANS TO ENTER THE AUSTIN COUNTY REGION

Most likely, the first European to set foot within the boundaries of what is now Austin county was Ren� Robert Cavelier,who set out on foot to reach the Mississippi River travelling northeastward from his base at Fort St. Louis, above Matagorda Bay.

The first Spaniard to reach the area may have been Alonzo De Le�n, governor of Coahuila, who may have ventured through in the spring of 1689 while searching for traces of La Salle's expedition. De Le�n returned to the vicinity in the spring of 1690 in the company of the Franciscan priest Dami�n Massanet on a mission to the Tejas Indians, traveling from Garcitas Creek on Lavaca Bay northeastward to the headwaters of the Neches River. His general route, which followed a crude Indian trace through southeastern Texas and is believed to have passed along the northern border of what is now Austin County, later became known as the La Bah�a Road and served as a major thoroughfare between the presidios at Goliad and San Francisco de los Tejas, near the site of present Crockett.

In 1718, Texas governor Mart�n de Alarc�n, having founded the Villa de B�xar and San Antonio de Valero Mission, crossed the territory of the future county on an expedition from Matagorda Bay to the missions of East Texas.

ANGLO SETTLEMENT IN AUSTIN COUNTY REGION (1820's)

Settlers from the U.S. began moving into what is now Austin County in the early 1820s with the founding of Stephen F. Austin's first colony. By November 1821, four families had settled on the west bank of the lower Brazos. By the fall of 1823 Stephen F. Austin and the Baron de Bastrop choose the site of the unofficial capital of the colony, San Felipe de Austin. The settlement quickly became the political, economic, and social center of the colony.

By the end of 1824, thirty-seven of the Old Three Hundred colonists had received grants of land. These early settlers were attracted to the well-timbered, rich, alluvial bottomlands of the Brazos and other major streams; the especially prized tracts combined woodland with prairie. Most of the immigrants came from Southern states, and many brought slaves.

COTTON PLANTERS AND SLAVES BEGIN ARRIVING IN TEXAS

By the late 1820s, prosperous settlers had begun to establish cotton plantations, emulating the example of Jared Groce, who settled with some ninety slaves on the east bank of the Brazos above the site of San Felipe and in 1822 raised what was probably the first cotton crop in Texas. In 1834 more than one-third of the 1,000 inhabitants of the future county were African Americans.

Soon San Felipe ranked second in Texas only to San Antonio as a commercial center. By 1830 small herds of cattle were being driven from San Felipe to market at Nacogdoches. Cotton, however, the chief article of commerce, was carried overland by ox-wagon to Velasco, Indianola, Anahuac, and Harrisburg.

After 1830, steamboats gradually began to appear on the lower Brazos, and by 1836 as many as three steamboats were plying the water between landings in Austin County and the coast. During the 1840s a steamboat line on the Brazos provided regular service between Velasco and Washington.

SAN FELIPE AREA BECOMES CAPITAL OF PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF TEXAS

The area around what is now Austin County played an important role in the events leading up to the Texas Revolution. The conventions of 1832 and 1833 were held at San Felipe and, as the site of the Consultation of November 3, 1835, the town became the capital of the provisional government and retained that role until the Convention of 1836 met the following March at Washington-on-the-Brazos.

SAN FELIPE BURNED IN 1836

After the fall of the Alamo, Gen. Sam Houston's army retreated through Austin County, pausing at San Felipe and then continuing northward up the Brazos to Groce's plantation.

On March 30, 1836, the small garrison that remained at San Felipe to defend the crossing ordered the town evacuated and burned to keep it from falling into the hands of the advancing Mexican army.

Residents fled eastward during the incident known as the Runaway Scrape.

AUSTIN COUNTY NAMED IN HONOR OF STEPHEN AUSTIN (1837)

In 1837 Austin County, named in honor of Stephen Austin, was officially organized. Although the burning of San Felipe left the town unavailable to serve as the capital of the republic, the partially rebuilt town became the county seat of Austin County. After a referendum of December 1846, however, Bellville became the county seat.

GERMAN IMMIGRATE IN NUMBERS TO AUSTIN COUNTY REGION

In 1831 J. Friedrich Ernst, a native of Lower Saxony, was granted a league of land on the banks of Mill Creek in what is now northwestern Austin County. Ernst described his new home in glowing terms in a letter to a friend in Germany, and his descriptions were reprinted in newspapers and travel journals in his homeland. Within a few years a steady stream of Germans began settling in Austin, Fayette, and Colorado counties.

In 1838 Ernst surveyed a townsite on his property on which the community of Industry arose. Industry is recognized as the first permanent German settlement in Texas.

Between 1838 and 1842 alone, several hundred Germans moved near the town; those not establishing permanent residence soon began rural communities throughout northern and western Austin County.

In some instances, as at Industry, Cat Spring, and Rockhouse, the immigrants founded all-German towns; more commonly, however, they formed German enclaves within areas previously settled by Anglo-Americans and often became numerically and culturally dominant.

Most of the early German immigrants were from provinces of northwestern and north central Germany; among them, however, were increasing numbers of Austrians, Swiss, Wends, and Prussians. Most soon acquired land and began cultivating cotton and corn like their Anglo-American neighbors, although many followed the example of prosperous early settlers Friedrich Ernst and Robert J. Kleber and raised tobacco.

The tobacco crop was either fashioned into cigars locally to be marketed in San Felipe and Houston�the activity that inspired the name Industry�or, during the 1840s, was sold to the German cigar factory at Columbus in Colorado County. In the 1850s a cigar factory was established at New Ulm in Austin County.

By the mid-1840s, Austin County had a reputation as a haven for German settlers which triggered a new wave of immigration to Austin County in the late 1840s and 1850s consisting largely of political dissidents, many well educated.

Among the community's cultural achievements was the founding of an influential German-language newspaper, Das Wochenblatt, originally published at Bellville by W. A. Trenckmann in 1891; the paper was later moved to Austin. Not until the Civil War did German migration into the county subside. By 1850 the county population included 750 German-born residents, 33 percent of the white population; American-born farmers outnumbered their German-born counterparts by the same two-to-one ratio. By 1860, however, German-born farmers outnumbered the American-born.

The steady stream of southerners arriving with slave property pushed the county's slave population steadily upward. By 1860, slaves accounted for 39 percent of the population. In 1860 twelve Austin County residents ranked among the wealthiest individuals in the state, i.e., as holders of at least $100,000 in property. Six residents held more than 100 slaves.

From 1824 to 1837 San Felipe was the only town in Austin County. By the early 1850s, however, Industry, Travis, Cat Spring, Sempronius, Millheim, and New Ulm had appeared.

In the mid 1800's, many Texas communities were nothing more than clusters of farms with a post office and general store near the center of the settlement. Despite the increase in steamboat traffic on the Brazos in the 1850's, the primary means of transportation was the ox drawn wagon. By the late 1850s, the first railroad arrived in the area (The Houston and Texas Central extended its main line northward through Hockley to Hempstead, in the eastern district of the county east of the Brazos, in June 1858). Cotton was shipped to the rail line by wagon from western Austin County crossing the Brazos at a number of ferries between San Felipe and the mouth of Caney Creek.

Most German immigrants arrived in Texas too late to receive free land, the distribution of which ceased in the early 1840s. Furthermore, most had been compelled to expend so much of their money on the way that they had relatively little to buy land and livestock.

In 1856 Germans near Cat Spring formed one of the earliest agricultural societies in Texas, the Cat Spring Landwirthschaftlicher Verein, which continues to today. Germans also owned few slaves. Yet, except in the case of a relatively small group of Forty-Eighter intellectuals, this circumstance was due far less to philosophical opposition to slavery�as many Anglo-Americans suspected�than to the fact that most German immigrants lacked the money to buy slaves. The few Germans who did own slaves were generally those who had immigrated during the 1830s and 1840s and had thus accumulated the requisite wealth.

By 1860 only about a dozen of Austin County's German residents were listed as slaveholders in the federal census reports; most owned fewer than five slaves, while the largest German slaveholder, Charles Fordtran,owned twenty-one. Many German farmers raised tobacco, the local production of which they soon dominated, in the belief that the crop required the sort of intensive care that slaves could not provide. German yeomen, moreover, utilized far more hired labor than did their neighbors, drawn from new immigrants, who continued to arrive. German farmhands, who usually preferred to work for Germans, could be hired more cheaply than slaves.

AUSTIN COUNTY DURING THE CIVIL WAR ERA

With the coming of the Civil War hundreds of Austin County residents enlisted in Confederate or state military units. State formations to which companies organized in the county were attached included the Second, Eighth, Twenty-first, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-fifth Texas Cavalry regiments, the First and Twentieth Texas Infantry, and Waul's Legion.

However, much of the rush to enroll in state and county militia companies, so-called "home-guard" units, had less to do with motives of patriotism than with the desire to avoid combat. Many German residents had immigrated to the United States to avoid military service in Austria, Prussia, or other European states; many Germans were reluctant to risk their lives in defense of the "peculiar institution" of slavery.

The Confederate government's adoption of conscription in early 1862 had a significant effect on the Texas settlers who were desperately trying to remain neutral in the conflict. Besides rushing to enlist in home-guard units, many draft-age males gained exemption from conscription as wagoners or teamsters. But as the war dragged on and exemptions became more difficult to obtain, men subject to the draft resorted to increasingly drastic measures. Some county residents fled the state for Mexico. Others, who could not abandon their families entirely, hid in the woods. Some of these returned to their homes at night to plow their fields by moonlight.

Some county residents serving with Confederate units deserted upon returning to their homes on furlough. The names of forty such men, most of them German, were published in the Bellville Countryman in December 1862. By late 1862 county enrolling officers were claiming that 150 Germans subject to conscription had refused to present themselves for induction.

Confederate officials took note of the situation developing in Austin county. It was reported that forcible opposition to conscription was being organized in the German settlements of Austin and surrounding counties. Gatherings of from 500 to 600 individuals, conducted in German to foil possible Anglophone spies, were said to have been held at Shelby, Millheim, and Industry in December 1862 and early January 1863. On January 8, 1863, martial law was declared in Austin, Colorado, and Fayette counties.

Several companies of the First Regiment of Gen. H. H. Sibley's Arizona Brigade were rushed from New Mexico to suppress the uprising. A detachment of twenty-five soldiers under Lt. R. H. Stone was sent to Bellville to arrest the ringleaders of the Austin County resistance. The detainees were turned over to local authorities; most of those arrested were German, but some of the principal conspirators were not. By January 21 the rebellion had been officially quelled and all who had been conscripted were coming forward for enrollment. However, the arrests left much bitterness.

The homes of several German farmers had been ransacked, prisoners had been beaten, and their families had been abused. This deepened the contempt of the Germans for the Confederate enrollment officers. Nor did the events of January end the search for subversives in Austin County.

In October 1863 Dr. Richard R. Peebles, a founder of Hempstead and respected local physician, and four coconspirators were arrested on charges of treason for having circulated a pamphlet that urged an end to the war. After brief stints in the jails of San Antonio and Austin Peebles and the other prisoners were exiled to Mexico.

Scores of German county residents loyally served in the Confederate Army. Hempstead, because of its strategic location on the Houston and Texas Central Railway, became an important assembly point for troops from throughout Central Texas. A Confederate military hospital was constructed at Hempstead, and three Confederate military posts were established in the vicinity; one of these, Camp Groce, was one of only three prisoner of war camps in Texas. At least five smaller military camps were scattered through the county west of the Brazos River.

When the Union navy tightened its blockade of the Texas coast, local planters shipped cotton to Matamoros in long caravans of ox wagons to be exchanged for salt, flour, cloth, and other commodities. Even so, expanded domestic manufacturing had to be relied upon to fill most needs. Several county businesses produced munitions: a gunsmith shop in Bellville reconditioned rifles and muskets for the Confederate Army; foundries in Bellville and Hempstead produced canteens, skillets, and camp kettles under contract with the state of Texas; the Hempstead Manufacturing Company made woolen blankets, cotton cloth, spinning jennies, looms, and spinning wheels. Nobody starved in Austin County during the war, but suffering was widespread, especially among families with soldiers in the field.

Unfortunately, the end of the fighting in the spring of 1865 did not bring the expected end to strife; Reconstruction in Austin County, as in much of the rest of Texas, was violent and chaotic. The war years had brought another expansion of the county's black population, as planter refugees from the lower South flocked into the area seeking protection for their slave property. Between 1860 and 1864, according to county tax rolls (which probably understate the matter), slave population increased by 47 percent to 4,702. Though some blacks entering the county returned after the war to the communities from which they had recently been uprooted, many others remained.

AUSTIN COUNTY DURING THE RECONSTRUCTION ERA

The war had scarcely ended before the federal government moved to garrison Austin County. From August 26 to October 30, 1865, Hempstead was occupied by elements of the Second Wisconsin Cavalry and several other units under the command of Maj. Gen. George A. Custer. After Custer went to Austin, Hempstead was garrisoned for a time by a small detachment of the Thirty-sixth Colored Infantry.

Two white companies of the Seventeenth United States Infantry were posted in Hempstead from 1867 to 1870. The garrison was controlled by the subassistant commissioner of the thirteenth subdistrict of the Freedmen's Bureau,which embraced all of Austin County and had headquarters at Hempstead. The troops helped ensure equal access to polling places and the court system, but their numbers were too few and their resources too limited to permit them to enforce the laws everywhere within the county.

Capt. George Lancaster, head of the local Freedmen's Bureau office in 1867, declared that racial animosities in the area were so intense that only a spark was needed to set off an explosion. Violent confrontations between federal soldiers and local residents were common throughout the Union occupation. The numerous reports in the bureau records of violent crimes committed against blacks by whites portray a campaign of intimidation conducted against the freedmen; with Republicans and Democrats struggling for control of the county's black vote, most if not all of these crimes were politically motivated.

The appearance of the Republican-sponsored Union League in the county in early 1867 outraged white Democrats, who responded by forming a Klan-like organization. The violence was most intense in the eastern district of the county, where the black population was concentrated; there the whipping, shooting, and even lynching of blacks became almost routine; few culprits were ever brought to justice. But blacks were not the only targets of white wrath. In March 1867 two soldiers were shot to death for what subassistant commissioner Lancaster termed the "crime" of wearing the federal uniform, "in the eyes of these white desperadoes a sufficient cause for murder."

In the spring of 1869 a white Republican newspaper editor from Houston, visiting Hempstead to address a black audience, was accosted by a mob and run out of town. Interracial riots broke out on at least two occasions in the eastern district near Hempstead in 1868. Yet with federal troops on hand to safeguard freedmen's rights, a number of blacks in Austin County were elected to positions in local government during Reconstruction.

In the gubernatorial election of 1869 black voters helped provide victory in the county for Radical Republican Edmund J. Davis. By 1873, however, as Confederates recovered their political rights, the Democrats had regained control of the county's electoral machinery; thoroughly intimidated, few blacks risked casting a ballot. The smashing Democratic victory that resulted signaled the end of Reconstruction and the permanent eclipse of Republican power in the county.

CZECH IMMIGRATION AFTER THE CIVIL WAR BOOSTS POPULATION OF AUSTIN COUNTY

Czech families began settling into Austin County with

the first Czech settlement being established in Cat Spring in 1847. By the 1880's, Czech families worked their way about 30 miles northward to settle in New Tabor, Caldwell, Sebesta's Corner and Snook. Others migrated westward into Lee County to settlements like Deanville and Hranice.

HISTORY OF CAT SPRING (1834)

Cat Spring, at the intersection of Farm roads 2187 and 949, on the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad and the west bank of Bernard Creek in western Austin County, was first settled in 1834 by German immigrants Louis von Roeder, Albrecht von Roeder, Joachim von Roeder, Valeska von Roeder, Marcus Amster, Karl Amster, and a handful of others. The settlement was named Cat Spring supposedly because a son of the von Roeders' killed a puma near a spring and the family named the area """Katzenquelle" (Cat Spring).

Many of these immigrants had been attracted to Texas by the letters of an earlier Oldenburg migrant, Friedrich Ernst, who had taken up land nearby in the valley of Mill Creek in 1831.

A German Protestant congregation was organized at Cat Spring by Rev. Louis C. Ervendberg between 1840 and 1844. The earliest agricultural society in Texas was formed in the town immediately after the Civil War.

WHY THE CZECHS CAME TO TEXAS

Reverend Arnost Bergman, born August 12, 1797 in Zupudor, near Mnichova Hradiste in Czechoslovakia immigrated to Texas and settled in Cat Spring in March, 1849, where he bought land and began to farm.

TEXAS HISTORICAL MARKER IN AUSTIN COUNTY: "People from Czechy began to come to America for liberty as early as 1633. First known Czech in Texas was Jiri Rybar (George Fisher) , customs officer in Galveston in 1829. Others arrived individually for years before letters sent home by Rev. Josef Arnost Bergman, an 1849 Czech settler at Cat Spring (9 mi.s), inspired immigrations in large numbers.

Josef Lidumil Lesikar (1806-1887) was instrumental in forming the first two large migrations, 1851 and 1853, with names of family parties listed on ship logs as Similar (Shiller), 69; Lesikar (Leshikar),16; Mares (Maresh), 10; Pecacek (Pechacek),9; Rypl (Ripple), 7; Coufal, 6; Rosler (Roesler), 6; Motl, 5; Jezek, 4; Cermak, 3; Janecek, 3; Jirasek, 3; Kroulik, 2; Tauber, 2; Marek, 1; Pavlicek,1.

With pastor Bergman's counsel, many of the Czechs began to farm in Austin County. Other immigrations occurred in the 1850s , and became even heavier in the 1870s. Czechs eventually spread throughout the state, gaining recognition for industry , thrift , and cultural attainments. To preserve their heritage, they succeeded in having a chair of Slavic languages established (1915) at the University of Texas, and later at other schools. Their ethnic festivals have been held in various cities for many years".

As Fredrick Ernst was responsible for a great deal of German immigration to Texas, so Bergman was responsible for much of the early Czech immigration to Texas. He too wrote home describing the land and resources in glowing terms. Bergman is generally recognized as the catalyst behind Czech immigration to Texas.

Also, Svoboda , a newspaper published in La Grange with a large circulation both in the United States and Europe, was also responsible for the large number of Czech immigrants settling in Texas.

Few Czechs became permanent residents of Cat Spring but only stayed long enought to raise several crops on a tenant basis and accumulate some cash, food supplies, horses, wagons and farming equipment before moving to other communities. Josef Arnost Bergmann himself moved on and spent his last years in Corsicana (buried there in April 1877).

In 1853 Josef Lidumil Lesikar and his family settled on some land near New Ulm after a voyage from Moravia which had lasted fourteen weeks. There with the aid of his four sons he built a log cabin for his family home. Lesikar wrote for a number of Czech publications, describing the situation in Texas prevailing at this time. It is said that these publications increased immigration to Texas, especially after the Civil War, when the greatest number of Czech immigrants arrived.

TEXAS HISTORICAL MARKER IN AUSTIN COUNTY: Born along the Czech-Moravian border , Josef Lidumil Lesikar received early training as a tailor. During the revolution of 1848, he became a spokesman for political freedom in his homeland. In 1853 he led a group of immigrants to the new Czech settlements in Austin County. Always opposed to slavery, Lesikar spoke out against secession and civil war in articles he wrote for Czech and U.S. newspapers, Lesikar married Terezie Silar (1808-1884) and had four sons.

Czechs eventually spread throughout Texas and the pioneer names of Leshikar, Sebesta, Smetana, Skopik, Shillet, Pett, Hriska and others may be found in many of their later settlements

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Czech immigrants continued to arrive in small numbers from northern Moravia and northeastern Bohemia moving onto small farms among the German population on the blackland prairie soils of Austin County. However, after the Civil War, the pace of Czech immigration increased; in the decade after 1870 alone more than 800 Czechs settled in Austin County.

The Czechs slowly found their Czech-Texan identity and founded their own uniquely Czech settlements.

CZECH IMMIGRATION PATHS

The common route for European immigrants was to board a sailing vessel at the port of Bremen, Germany; then sail to the port in Galveston, Texas. From Galveston, the immigrants travelled by steamship to Houston and then bought an Oxen and cart, loaded up their belongings and the family walked and rode the 60 miles to Cat Spring in Austin County.

Cat Spring-a One store Town

In the early 1850s, Cat Spring was little more than a single store, owned by Jan Reymershoffer. Reymershoffer had sent back letters to Moravia describing Cat Spring heaven attracting a few

Czech immigrants who worked as tenant farmers for the Germans that had earlier settled the Cat Spring area . Once the Czech tennant farmers had enough money to buy land of their own, they packed up in wagons and moved northward to such settlements as Snook, Industry, Caldwell, Deanville, and Hranice.

CAT SPRING POST OFFICE (1878)

The Cat Spring post office was established by 1878. By the early 1890s the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad linked Cat Spring with New Ulm to the west and Sealy to the east. At that time, the town was moved to its present location leaving little in the way of buildings from the original Cat Spring community.

This is a work in progress. Bookmark this page and come back often. If you have old photographs of Cat Spring, Hranice, Dime Box, Snook,Deanville or other nearby Czech settlements , please email me a copy and I'll include your photos and stories on one of my Czech webpages.

Thanks

Leonard Kubiak

For questions or comments, send me an Email at lenkubiak.geo@yahoo.com

For questions or comments, send me an Email at lenkubiak.geo@yahoo.com

|

![]()

![]()